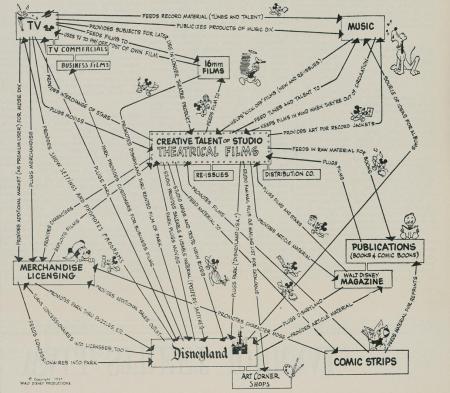

Walt Disney had left extensive notes and audio recordings concerning his experiences making animation, which were stored in the Disney archives. Walt Disney, however, left another, arguably even more valuable, recipe for his company. This was a strategic recipe or we can say a corporate theory of sustained growth. This corporate theory is largely captured in the adjacent drawing also from the Disney archives, published in 1957. It depicts a central film asset that in very precise ways infuses value into and is in turn supported by an array of related entertainment assets. This 1957 map of Walt Disney’s vision defined his company’s key assets, including a valuable and unique core, and identified patterns of complementarity among them. It implicitly revealed the industry’s future evolution and provided guidance concerning adjacent competitive terrain that Disney might explore. The asset and capability combinations that emerged from the theory have evolved with time, but the theory itself has not fundamentally changed. The fundamental patterns and the underlying insight and intuition of the firm is still quite consistent. The strategic vision that Walt long ago composed has revealed a succession of strategic possibilities that have fueled a remarkable record of value creating growth.

The image depicts a range of entertainment-related assets—books and comic books, music, TV, a magazine, a theme park, merchandise licensing—surrounding a core of theatrical films. It illustrates a dense web of synergistic connections, primarily between the core and other assets. Thus, as precisely labeled, comic strips promote films; films “feed material to” comic strips. The theme park, Disneyland, plugs movies, and movies plug the park. TV publicizes products of the music division, and the film division feeds “tunes and talent” to the music division. Walt’s theory in words might read: “Disney sustains value-creating growth by developing an unrivaled capability in family-friendly animated (and live-action) films and then assembling other entertainment assets that both support and draw value from the characters and images in those films.” The power of this theory was perhaps most vividly revealed following Walt’s death. Within 15 years leadership at Disney seemed to lose sight of his vision. As the company’s films markedly shifted away from the core capability of animation, the engine of value creation ground to a halt. Film revenues declined. Gate receipts at Disneyland flattened. Character licensing slipped. The Wonderful World of Disney, the TV show that American families had gathered to watch every Sunday evening, in a nationwide embrace, was dropped from network broadcast. By the late 1970s, the Disney franchise many of us had grown to love as children had all but disappeared. Attesting to the depths of Disney’s disarray, corporate raiders in 1984 attempted the unthinkable: a hostile acquisition of the company with a view to selling off key assets, including the film library and prime real estate surrounding the theme parks. The capital markets embraced this idea, leaving the board with a critical choice: sell Disney to the raiders, who would pay a significant price premium but dismantle the company, or find new management. The board chose the latter and hired Michael Eisner. Eisner rediscovered Walt’s original theory and used it to guide a heavy investment in animated productions, generating a string of hits that included The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, and The Lion King. Over the next 10 years Disney’s box office share jumped from 4% to 19%. Character licensing grew by a factor of eight. Attendance and margins at the theme parks rose dramatically. Disney’s share of income from video rental and sales soared from 5.5% to 21%. Eisner opened new theme parks, made further investments in live-action films, and expanded into adjacent businesses consistent with the theory, including retail stores, cruise ships, Saturday morning cartoons, and Broadway shows. By essentially dusting off Walt’s theory and aggressively pursuing strategic actions consistent with it, Disney won growth in its market capitalization from $1.9 billion in 1984 to $28 billion in 1994. That cycle has repeated itself in the years since: Although the move into Broadway shows was complementary to animated films, character licensing, and theme parks, other strategic moves, such as the 1988 acquisition of a Los Angeles TV station, the 1995 purchase of Cap Cities/ABC, and the 1996 purchase of the Anaheim Angels, failed to reflect the theory’s logic. Meanwhile, Eisner allowed the core animation asset to atrophy again as the company failed to keep up with technology trends and the best-in-the-world animators migrated from Disney to Pixar. Disney gained access to their skills through a contract, but the relationship between Disney and Pixar grew contentious and was finally severed just before Eisner stepped down, in October 2005. His successor, Robert Iger, quickly moved not merely to repair the Pixar relationship but to acquire the company, for more than $7 billion. Disney’s recent acquisitions of Marvel and Lucasfilm fuel this central asset, although they carry the company into somewhat unfamiliar terrain: The Marvel and Star Wars casts are quite different from Disney’s traditionally princess-heavy character set. Whether this strategic experiment proves to be value-creating remains to be seen. But Walt Disney’s road map for growth has clearly endured long past his death, providing a remarkable illustration of posthumous leadership. This article was actually a part of the HBR article What Is the Theory of Your Firm. I actually found this part so fascinating that decided to blog it. Hope you enjoyed!